And If It Be Mean

Norma Gay Prewett

___________

“Hey, I’ve become homeless! By choice!” Rosie sang into the phone, her words making exclamation points. “But I’ve found a sleeping bag, and it’s red plaid, the warmest color,” she said, as if in all caps. On the other end of the phone line her sister Lana would be curled on the brocade loveseat where Lana and their brother, Max, had chatted over coffee during the brief months he had lived with Lana before his death. Rosie was being insensitive, since Lana shared with Rosie her daily struggles to keep her home ever since Lana’s last temp job went South, literally, to Mexico. But sometimes they buoyed each other up this way. Both had survived scares with a half-dozen deadly diseases—not hypochondriacal, but screwy and rare and symptom-based—in the same number of months and they were always over the top, at least figuratively. They perked pretty hard and high, as they often noted.

“Doubleya tea ef,” said Rosie, pronouncing each initial as if writing it on Facebook. She heard Lana clink the side of her coffee pot against the sink, though it did not make a breaking sound.

“Fudge,” Lana muttered, then, “Hold on.”

She had put the phone down. Rosie was on speaker—hollering into a cave.

“Didn’t break,” said Rosie. “Focus. Back to me here.” As she spoke, she packed the red plaid sleeping bag as if she were traveling to Europe instead of two measly hours away. Two hours and a lifetime, she thought, dramatically. She stuck a few clothes—warm, durable things—into the interior and intended to make a giant roll, like the scroll of a snail, on her back. She liked the image, along with the one of herself holding a gnarled walking stick with a bear whistle purchased on one of her recent trips with Lana to Sweet Springs, Arkansas, not far from where they had grown up. They took occasional “tour des morts”—death trips to visit their relatives’ graves. As she heard her sister prepare her end of the coffee ritual, Rosie realized that she needed coffee too—her last vice. She had given up a loved habit each decade since she turned forty—on her birthdays—smoking, drinking; fatty foods all had fallen and she mourned them as the Japanese do their aborted fetuses. Had even erected little monuments in the pet cemetery in the garden. She wondered what the new owner of her house and land would think upon discovering them.

The dear old house had sold nearly too quickly—before she could have misgivings, before the divorce was quite final. And her self-inflicted homelessness wasn’t quite real either. She had decided to front the wilderness and see “if it proved to be mean”—as her college idol Henry David Thoreau, the sour old bachelor, had said about his sojourn at Walden. While she was married, Rosie and her husband Sven had purchased a few acres smack in the midst of the rural Wisconsin coulees. Because they had made the youthful mistake of committing to rentals real estate, which now “owned” them in town, they had proudly refused to improve the cabin much, as though its inconvenience made it holier. Lana was in the process of shedding the rentals too—going down the road of trying to lighten her psychic load, as she considered it. It was really Rosie who loved the cabin. To Sven, it had been lean-to shelter between trout-fishing trips. Their son scorned it, a town kid all the way, and now, at 23, he was launched. Rosie was becoming inessential to anybody but Lana.

“Halloo-o-o-o-o?” Lana called into the phone. “Did you fall in?” She had caught Rosie using the john while phoning—something so coarse neither of them could even bear it in movies.

“Here!” said Rosie. “Hey, do you remember when I used to pilgrimage to Walden every year?” Those had been fine days, usually in Spring when she was visiting some boyfriend or other in Boston. Rosie had always taken the train, or to be Thoreauvian, it always took her. The Lakeshore Limited was a lot more elegant in those days and the whole thing was romance on the half-shell to her heaving heart. Daffodils would be just blooming in the soft seacoast winds, whereas they were months away in Wisconsin, so she always purchased a bunch, along with sandwiches and hot chocolate, to take to her traditional lunch with Henry. His part of the conversation was a bit muted, there in Sleepy Hollow cemetery, but she propped herself on his grave, his simple “rising in the ground” limestone headstone, and chatted him up. Generally, there had been pilgrims there before her, leaving their own tokens of love, since all of the Alcotts and many other luminaries were housed in their tombs all around. It was a celebrity cemetery.

“Did I ever tell you I think Alec was conceived there?” Rosie asked suddenly. She knew her sister was listening and hoped she was smiling what she teasingly called her “pickerel” smile. “Did I?”

“I recall that he was a little underwhelmed about the honor,” said Lana. “Didn’t you take him back there when he was five or six? You hadn’t even taken the poor kid to Disney World but expected him to be thrilled by a big old deserted pond and a replica shack?”

Rosie glanced at her watch. “I gotta run,” she said as she mulled over whether she was offended or not. They pushed each other’s buttons and refused to get too riled about anything short of outright hostility. As adults, Lana trailing Rosie by two years, they had fought and fallen out only once or twice that Rosie could recall, and the searing pain of her sister’s rejection had sent her to her bed. It was worse than any of Rosie’s string of men leaving her emotionally bereft. Lana was nearly, besides Rosie’s son, the only person left above ground that Rosie loved unconditionally, as the therapists say. Their family choir was thinning. They were now orphans, for instance, their parents having died within a year of each other.

Pausing halfway down the curving oak staircase, Rosie paused to peer past a stained-glass piece she and Lana had made together and hung there. She wondered whether to pack and move it. The closing for the new owners was nearing. Rosie would miss this view, which was regularly lauded with sunlight or shot through or chiarascuroed by mist, snow, rain. Now, it was deep November, a month she had never had any use for before, but which now gave her solace. It seemed fitting that her former husband of twenty-five years had dumped her in the Fall, the time she formerly would have been filled with anticipation, stocking her plaid pencil boxes and thermoses for the coming year of teaching, until that was yanked from beneath her by his insistence on her early retirement. He had promised in sickness or in health, but Rosie had never been totally healthy and so maybe Sven figured they were even. That Girl, his Lewinsky, his Jennifer, had come to her in the form of a photo on his iPhone. He was a wannabe photographer, so at first, having ironically borrowed his phone to call their child, Rosie casually thumbed through his photos just out of boredom. One showed a girl, much younger than Rosie, encased in gauzy light, studying, on a train. Okay, she had thought, just a “grab shot” as Sven called his furtive pics. Then, before he could grab the phone back, realizing his mistake too slowly for Rosie’s stiletto-like eyes, another shot of the same girl in his rented bedroom in Chicago. Here, he had posed her in exactly an attitude that Rosie had been posed in years before when they were courting—hair tossing, eyes slanted and narrowed, mouth slightly open. It was as if his parallel life—and they had known it would be a potential threat when he had been economically exiled to a city more than a hundred miles from their home to spend all weekdays, and some weekends, working—also included a surrogate her. It was all such a cliché—the midlife crisis and the younger, fertile, chippy.

“Fiddle-de-fucking-dee,” she said in her Scarlett voice, “I’ll fucking think about that tomorrow.” Or maybe never, she thought. Would never be too soon? Until the tenth of never… She went downstairs thinking, “The new me should abandon ‘Fuck.’” She had mused aloud to Alec one day, who had barely known his grandparents on her side, that the worst she ever heard come flying from either parent’s mouth was “dadgummit,” or occasionally “that stinkin’ thing.” These were euphemisms, of course, with the same cadence as the words they replaced, but as Southern Baptists, they would no more swear than they would tango. In Rosie and Sven’s modern, smart, sophisticated home, they swore like sailors, though generally keeping it in its place—the hearth, the bar, the cars. It was a habit—like eating the whole bag of Oreos—and Rosie needed to be mindful and shed it as she had shed other mindless habits. Maybe mindfulness to language was going to be her seventh-decade shedding. At any rate, there would be fewer opportunities to offend anyone. She imagined herself a self-sufficient hermit out there on the land, a female coot.

Rosie swung open the hen-house door slowly, amazed anew that she and a few determined Back-to-Earthers had managed to convince the city to let her have backyard chickens. The new owners were going to pull the coop down, but had given Rosie time to relocate the chickens. The cabin was the perfect place. Pullet Surprise, her Buff Orpington hen, was wary of change. Even when Rosie left the coop door wide open, Pullie stepped one dinosaurus claw over the sill at a time, glancing nervously back to the warmth of the 200-watt bulb that kept her and her water from freezing. Her sister-wives had all been predatored by some wily critter that had breached their security, violated their castle, in the night. Had it happened now, Rosie thought, during her own newly acquired self-sufficiency, she could have done battle with her shootin’ iron. One of the first things she had bought was a shotgun in prep for her new isolation. It terrified her, but she was not going out there without protection. Several trail cameras had now recorded what had just been a tantalizing rumor before—cougars were making a comeback in Wisconsin. Their ghostly lithe and perfect killing-machine bodies showed opaque but hard to believe, their eyes gleaming like the Tyger, Tyger in the forests of the night. Her cabin land—now it would be all hers—would have been her choice had she been the big cat. It had several ramshackle, but still sheltering outbuildings whose doors stood ajar as often as they were closed, and an overabundance of mice and groundhogs and any other game, a smorgasbord for even a lazy cat.

“Come on, Chickiepoo,” she warbled to her tidy little pet. “There are lots of you where we are going. It will be like homecoming for you.” Rosie nudged the hen’s soft bottom with her hand, trying to convince Pullie that the extra-large cat carrier was cozy, not scary. Soon she would have to stuff her in like laundry in a hamper, but preferred persuasion. This particular chicken had been Rosie’s “familiar” in the marriage, her folly barely indulged by her fastidious husband. While the hen was laying, she was tolerable, but Sven’s mantra had been, “If she ain’t layin’, she ain’t stayin’.” Even before the most unoriginal sin, Rosie had mulled that motto. Though of course Sven didn’t talk like that, being an educated Scandinavian, not the hillbilly stock she herself came from. He was uncomfortable with displays and flash. Sven drank to let himself flirt with people a little, whereas Rosie was all sparkle and outrageous behavior. Once, they thought it completed them. Now they saw, belatedly, that opposites collide, not attract, and the iPhone photos had sent them careening out of orbit one last time. But he had been good with finances—taking risks Rosie could never have taken because she distrusted stuff in equal measure to lusting after it. Never had a pot to piss in or a window to throw it out of as a child, and now Rosie was conscious of how quickly things could dissolve and go up the chimney, down the spout, any other cliché that was worn out but had once been so true that everyone adopted it.

So they had acquired stuff—houses, autos, even a couple of sailboats, so that their life, like Sven, was big and heavy. When Rosie had taken her teaching job in Wisconsin, she mused, she, even tinier than she was now at five feet, 110 pounds, felt terrifically weighted down by the contents of the purple VW Microbus in which all of her earthly belongings had been packed. Two years later, she co-owned several properties which became for a while like the restraining garment people use for autistic children who feel out of control—weight like the body of the big man she had married. It had worked for a long time. Babies like to be swaddled, and now, it turns out, dogs can be covered with “thunder-shirts” so they feel safe in storms. Rosie just needed to be light again.

She patted the side of the Pathfinder, the sturdy good old Leatherstocking car/truck with 200,000 on her, and made her promise to get up those Amish hills one more time. Rosie animated her world, naming the unnamed—briefcases, cars, writing pens. She imagined she could hear trees mutter as they grew if she lay her head against them. And one talks to one’s friends.

* * *

After having driven most of the 100 miles, she topped the final hill and liked all she surveyed, as usual. Below her, the clotted, dotted, spotted Wisconsin dairyland dozed or maybe had not yet unfrozen from a chilly, leaf-twirling morning. Blue chicory and milkweed pods were frosted and bowed and seemingly as arthritic as she felt. The streams, being spring-fed, ran clear, black, and cold all year. She would have to ford one of these—an Irish ford it was called when you drove through water—to get into her land. The county had refused to let them bridge it, so having previously stayed there alone, at the first splat of rain, she had scurried like a goat to her car and crossed to the safe side. Rosie recalled how Sven had just shaken his head. He had seen her reduced to jelly by storms, practically frothing and bluing with fear. Now, though, she intended to hire a project out—a chopping of stairs up the long steep rocky bluff that backed the cabin and affixing of cable, a handhold, so that when the frequent flash floods boiled the mild stream like rolling thunderheads, she always had a magician’s trapdoor up to the highlands.

Sven had known that what could rear itself dramatically could also fall precipitously—that within an hour the former bubbly cheerleader of a creek could be a tsunami, and then subside to its former peppy self. She knew it in her head too, but not in her bones, not in her stomach. The creek was as treacherous as a person—she now knew quite a lot about what can lie beneath.

Smiling, since out here she was always smiling, Rosie lifted gear from the rear of the Pathfinder—the chicken carrier, a too-big chainsaw, barn boots, gloves of the silly gardening style, some late bulbs she wanted to plant since the squirrels and moles sometimes took three of four, her shotgun, heavy pack, and a gallon of water. Utensils, mostly blackened cast iron and sturdy stuff, were already stocked at the cabin. As she prepared to horse her goods and provisions onto the high porch, the first flakes of snow tipped her face back. Where aspen leaves had been, and where the thirteen sky-tapping hemlocks still glowered, now began the shivering silver of sleetish snow. It made her think of Christmas, which momentarily made her feel desolate—since she was now without plans that before had been assumed—but she shook it off. She was at the Piney Woods. Rosie forbade herself to look back or down. She was going to be always, as the crazy man who announced moon and planetary phases on the television said, “looking up.”

An hour later, there was a solid inch of real snow. But, okay, she had coaxed a one-match fire out of the red Vermont Castings stove, a skill Sven had taught her. Why was everything prefaced on Sven? Well, she reasoned, twenty-five years wouldn’t just vanish. But she would have to break that link like a coyote chewing off its foot—nah, more like an escaped slave hoisting her shackles onto a tree stump and lofting the ax again and again. “Oh, for Pete’s sake,” she warned herself. Rosie didn’t mind talking aloud, even singing aloud to herself, but she didn’t really laugh aloud for some reason. She wondered if she would become her grandmother, a true Ozark hill woman who had muttered like a nervous hen all day and night.

Rosie cut first one log and then another down to fit the tinier maw than the former fireplace had had. The fireplace had been excellent in every way except the practical way. Floor to ceiling, five feet across, made of fieldstone, it was straight out of central casting for a rustic cabin. But it sucked heat from the one-room cabin like someone huffing helium from a balloon and when, after ravaging floods had violated the cabin two years in a row and they had determined it needed to be hoisted, the fireplace had been a casualty.

Rosie had cried and had noticed that Sven had turned his back and busied himself as the house-movers raised the spikes of the Bobcat to pull the fireplace down. The tiny wood stove was a trooper. With the help of a heating blanket, she was toasty in a few minutes.

Then, the noises began, bringing memories down the stove pipe and dancing lewdly before her as she perched in her Amish rocker. She was suddenly ambushed by times when Sven and she had sat there, his wrapping her and himself in blankets, chaffing her feet in his hands, touching her hair. Her hair was true silver now—to the other woman’s chestnut curls. Rosie did not know whether she herself was still cute or not. Pictures shocked her as she saw her mother as an older woman staring back at her with her sweet Irish blue eyes and pretty skin, but also potbelly and Frida Kahlo brow. This new woman … well … Rosie slammed the open stove door with more vigor than necessary and settled in.

* * *

The following morning, she was feeling smug for having survived the cabin by herself with all its wild noises at night. During the day, the most she had ever seen roaming were a couple of twin deer that haunted these grounds, but at night it was Wild Kingdom out there. It had been this kind of ordinary day when Rosie first spotted the bootprints. Curiously, as fear sometimes does, her first thought was of the fake Santa bootprints Sven and she used to trump-up to convince their tiny son Alec that Old Saint Nick had visited and somehow shinnied down another skinny stove-pipe, leaving his plain print in the ashes. But her second thought was more sober—there had been someone since snowfall right outside her door as she slept. Was it hunting season? Yes, that was it, but no smart hunter would come right up to the door of another person’s cabin. Too many trigger-happy greenhorns out here. Since coming onto the land meant crossing icy, fast water, not too many lost travelers ever bothered. There were cottages up and down the road—much easier pickings. And, had her first premise been right, the land was clearly posted as being off-limits to hunters. Well … maybe the prints were those of the handyman, checking up on her. Maybe Hank the handyman. Yes.

Rosie passed the next day in town, a perfect Wisconsin small town named Bud, a name as curt and straightforward as the town itself had once been. It had been discovered now, much to the chagrin of older finders like herself. Newcomers were “cute-ing” it. The things some of them fled in cities were now here—the “shoppes” where stores once stood; niche-y markets instead of hardware stores. There were fewer milking implements in Elmer’s True Value and more art quilts. Was she getting crotchety, she wondered. After all, everybody but the Chippewa were fairly recent immigrants, even the Amish, here. It was a matter of degree. But along with progress and convenience came price hikes. The town was getting to be what the handyman Hank sometimes called “mighty spendy.” The word had been punctuated by a splat of chewing tobacco recently since his wife had laid into him about smoking, so he had begun to chew. (Rosie thought of her Dad’s witticism: Many men smoke, but Fu Manchu. Her head was like a gumball machine. The thoughts just dropped down on her tongue and rolled out of her mouth willy-nilly.) Inevitably, a Walmart superstore had swum into town thrashing its gigantic nasty tail of straightened-out roads and cropped-off hills behind it. Newcomers hated it and old-timers loved it. Just the opposite of the progression that was happening everywhere else. But the store had this shade of blue she wanted for her new abode. It seemed like a small sin.

Once inside, though, Rosie became drowned again in the sheer excess. Her new skin, her new self-reliance, suddenly seemed stingy, though she knew the pretty comforters and things were all made in China, probably by kids who could be poisoned by dyes so that she, lucky, lucky she, could buy, buy, buy.

She set the gallon of paint down and quickly strode out of the store. The friendly Newcomer Co-op would be more her speed. She had brought her knitting. She knew the locals still eyed her curiously, though she had connected on some level with many and a few knew her name. Hank’s wife worked here, but Rosie was not sure whether the woman liked her. Nobody knew where she fit, neither pig nor fish, and neither did she. Rosie dressed like a lumberjack, but sometimes drove a Saab. She had dirt on her boots, but also an expensive haircut. Her knitting wasn’t pretentious. Long scarves of garter stitch were all she had attempted. But the yarn was expensive—always pure wool.

By the time she got back to the land, she felt singed if not entirely burned out. The days ahead stretched at once glorious and foreboding. She suddenly recalled a short story she used to teach in which a young wife learns that her husband is dead and then that the death had been misreported—all during the space of an hour. In the story, the young woman dies of “the joy that kills.” Like her, Rosie was “free, free, free” and the thought frankly terrified her.

On a whim, since the night was drawing in and she wasn’t quite ready to abandon herself to the cabin and her friends the mice—and because she remembered that she had not fed Pullet Surprise after she had installed her in the out-building closest to the house—Rosie pulled the truck into the lean-to, but then walked back to visit the creek, a habit like vespers for her. Around the edges, ice had begun to creep like cataracts over the good eye of the water. Some looked cracked, as if weight had been upon it. “Deer,” she thought reasonably. But she began to back her body toward the cabin. When she heard a sudden buzzing, there was no way to fit the sound into her surroundings. Swinging about, realizing she had no weapon, she instinctively brought her hands up. The incongruity of the cell phone swinging around blinking and buzzing made Rosie cock her head like a spaniel. “What the what?” she muttered, proud of avoiding “fuck.” Then, as soon as she bent to pick it up, it hit the bank and slid into the churning water. Waterloo water. Her gullet and heart traded places as she felt the “sick with fear” that one reads about. It was not right. No place for this here. Her phone service had never stretched this far and she knew that anybody who knew the place knew that too. Rosie could not bear to open her back to the darkness while she fished the phone out, nor could she stand to leave it in. She settled on a crabbing, sideways motion, wetting her arm to the elbow, but securing the now-deceased mechanical.

Her progress the five feet or so to the comfortingly warm, popping, car was that kind of creepy movie moving. She slammed the door and locked all four. It was a rough and ready truck, but had power windows. Her arm had started to ache from cold and the slight rise that she usually took in one quick spurt to clear the creek in four-wheel drive was made difficult by a standing start and two inches of snow. But there were no tire-tracks other than her own. Still, she pulled as close to her makeshift coop as she could fit the car inside the shed and slipped out, leaving the comforting motor running with the headlights aimed. Stumbling, she discovered Pullet Surprise—dead at her feet. The hastily rigged warming light still shone like a benediction overhead and there was little blood. Rosie nudged her with her boot heel, starting to cry. A fox, a weasel, a dragon—she wasn’t farmer enough to know—had surgically taken Pullie’s head. She had heard that chimps when they fight frequently tear off the face as the thing that controls. And headhunters of course take that thing in which resides our power. Stupid thoughts and what if the thing still lurked here? She raised her foot to the high floorboards of the Pathfinder, grateful as she had ever been for normal technology, but not before she saw a single, still-slightly-smoking cigarette butt in the snow. Rosie tore sod driving to the house. She switched on the porch light and hurtled into the cabin, finding the key faster than ever before. Once, she had locked herself out by misplacing a key, so now always stationed one near the door—where any fool could find it.

With one sick thud, all four doors and the trunk locked from the jarring. The Pathfinder was still running with the car keys now locked inside. It had long been a problem with that car. A simple jarring of any kind would trip the automatic locks. It had been annoying at home, but at home, they had kept a second set of keys.

Rosie tantrumed. She screamed all the words she had resolved to cleanse from her new vocabulary. Crazily, she felt like hollering to the Universe, “You want another piece of me?” But she didn’t do that, needing to comfort herself as a newborn must learn to settle him- or herself down. Self-pity was a real spike-studded tiger pit for her. Passages from Hemingway, maudlin passages, not even his best, suggested themselves to her. “It kills us all. But if you are strong and brave it will kill you too, but be in no particular hurry about it.” Wasn’t even correct and she was none of those big things anyhow and this was her cabin and her land and three miles from town and she had a land-line, a life-line, after all. Oh em gee. Good grief. Except that she didn’t. Her neighbors were just across the road, but up a road so steep that she could barely navigate it in a car, by day, and could no more have trod up there now than she could fly over the moon, as her mother used to say. She had locked the gate and was sure they couldn’t know she was even there—so rarely did they visit—and then nearly never after the summer was over. They might see smoke from the fireplace, but like she and Sven, they were city people who had enough money to keep their cabin, but frequently traveled. The ugly white sixties wall-mount phone didn’t offer a dial-tone more than a second. Some bad movies really do come true. She remembered then. Before the fatal finding of the photos, Sven and Rosie had put the cabin phone on vacation mode.

Hands shaking, she found the Korbel far back in a corner of a cabinet where it’d been hidden from Alec and his pals, who were afraid of mice and would never grope back behind the traps. All of this could be explained, she explained to herself like a brain-injury patient. If her life were indeed a novel, it would all have a perfectly inevitable-seeming ending—once it was safely over and the blood pressure had returned to normal. The ice in the cube-making refrigerator—oh yes, they had some luxuries—let down suddenly and she felt a quick warm flash of urine break forth. Good God, how she wanted something as simple as a television, a radio, right then. Part of the idea had been to rid herself of what Faulkner called “the lifeless mechanicals” since Henry David, even if they had been invented, would have abjured them. What was it he said about clocks? She had brought the bible, Walden, with her. Maybe it was what she needed right now.

Did Thoreau drink? She thought not. He saw tobacco like the Native Americans, whom he respected, as a ritual, she believed. Well, I’m not him … he … or what the hell, she thought. Rosie had brought the squat, faceted Korbel bottle, a Christmas special bottling, with her and now tried to keep all sides of her body facing out as she made her Jack London fire. It leapt and she leapt. It bared its little oranged teeth at her, then sulked. “Stinker,” she said. Rosie threw the box of matches at the flame and it rose up and bit her. There were more matches. Weren’t there? The winking tinder had caught though and she fanned it quickly. Her toes and fingers ached. She felt in her pocket for another glove and found the doused cell phone.

A drink of liquid-fire brandy and she set the bottle down. This was a clean, if not particularly well-lighted place. Another indulgence was electricity, she supposed, and Rosie thanked herself that she had prevailed when Sven had wanted to put that utility on vacation mode too. She fumbled in the mouse-turdy drawer—show her the woman who can completely eradicate those little s.o.b.’s—for the hair-dryer. It was absurd to think that one can save a soused phone at all, much less after all this—how much she wasn’t sure, but a long—time. But it was a good, solid practical thing she could do to settle, settle, settle her twirling brain. She slipped the memory card out and dried that first. The phone was a cheaper model that probably—obviously—did the one thing phones are supposed to do much better than the Cadillac of phones she owned. The ones with apps to read her temperature, mix her drinks, hoe her garden, but which rarely performed the one task it was meant to do—make phone calls without dropping them.

Carefully, Rosie slipped the case apart and began gently driving the water droplets out. “Wait for it,” she murmured and realized her own voice comforted her somewhat—like the soft murmuring of her hen—oh, her hen. Well that, that was just Nature. Nature smoked cigarettes. She had crazy thoughts about DNA and actually entertained the momentary lunatic notion that she should go out there and grab that butt before the cold froze the saliva and rendered it … what? She had no idea, never listening in science class once things got hard. Inside the second tumble-down shed, the Pathfinder ceased running—out of gas. She missed the comforting, domestic, familiar sound terribly.

Her perfect plan, her sunny day plan, and oh how Henry David loved the sun as a symbol, had been to come here (“go there” at that time) and “front Nature.” Now, it appeared to have fronted her, but Korbel was giving her liquid courage and fire enough to front it back. Rosie put the cell phone back together as a clockmaker might. The only place a cell phone had ever worked on the land was out at the pole shed, while one touched metal like some crazed Ben Franklin. She pulled apart her crazy lace curtains. Now that the cabin was four feet off the ground and the windows another two feet up, it would be a bad tall dude indeed who could peer inside flat-footed, but the curtains gave her a good feeling. Nature might be red in tooth and claw, as she had just rediscovered, but she could at least put a nice blouse on her part of it. Man, she was getting slurry. That first little alcohol lift had blurred into slow motion bravura, the feeling at which she first had learned to stop and savor, then had unlearned it, then had quit after it had tipped her into situations she squirmed to recall, even fistfights.

She slipped into her parka—it had Nanook-like rabbit fur around the hood and cuffs—and grabbed the cop-grade flashlight, grasping the phone in her gloved other hand. It felt like safety—unless the intruder really were an animal. She looked at the shotgun, unloaded, and grasped it under her arm too.

The pole shed was always locked and stood one-hundred feet, she guessed, from the cabin. Congratulating herself on her drunken good memory, she felt for the keys before slamming shut the cabin door. She heard the wall phone plummet to the floor. Big deal, she thought. Useless mechanical.

It had snowed a little more since she had come home, but the night was blessed with a sun-like moon and the tall firs strangled the beams on the snow. It was pretty. Something small skated away from the light and she fought her instinct to slink back to the cabin. Rabbit, rabbit, Rosie thought. “The hare crept … something … through the frozen grass.” Whom would she call anyhow? Lana, of course. Or the owner of the phone? She reached the shed door and tugged it open. Smells, comforting smells of man-stuff—gasoline and oil and rope and such—greeted her and it felt almost like it did in the daytime. Then, she smelled another thing. It was cigarette smoke—recent cigarette smoke. It seemed insane to say so, but the final deal-breaker, more than the supposed infidelity with Sven, had been the damned cigarettes. The smell choked her now that she self-righteously did not smoke.

It is uncomfortable at least to feel the contradictions life is always strewing like candy-corn wrappers at a carnival and not want to say to this old crone Life, “Stop that. One feeling or the other, please.” Her Swiss Army knife, handy former husband who knew quality when he saw it with the broad and fatal exception of his new late middle-age squeeze, leapt to mind with concealed practical blade unsheathed. Had her heart been as weak as doctors for a while thought it might have been, this would have stretched its endurance to the limit. But Sven waited until she had stepped into the range of the motion light before coming out of the shadows. He stepped over to her, towering on purpose as she used to tease him, and with the trained hands of a former karate player, grabbed the shotgun barrel, which she had not the wit or quickness to train, and pointed it. Then, with his free arm, he swept her, not toward him, but aside.

Behind her, a cat, large as a St. Bernard, collapsed in the snow, Pullie’s little body in its jaws.

Nature is corny, but not perfect. Sven had arrived the night before, but knowing her fury, had not shown himself. He had camped, obviously, in the unheated shed, building a careful fire in a kettle grill they had kept there. The one window was slightly cracked to aerate the place and she took some quick satisfaction in knowing he had suffered in his work clothes—his junior executive suit covered only with a windbreaker. Now, when they should have climbed inside the warm Pathfinder, which he had discovered running and feared the first most obvious thing—her suicide—Rosie became furious instead. How could he risk her heart like that? What the hell and when and where? Sven waited her out as she sputtered terrified and furious accusations, shame-faced and barely breaking in—not defending himself.

Yes, he said, he had finally persuaded Lana to talk to him, but no, she had not ratted out any details. That, Sven said, he had put together by himself. He had tried to call, especially after he had dropped his loaner cell phone in the drive and somehow missed it when he went back to look. Sven had walked the three miles from and to town, cutting through the brush because, well, because Lana had let him know that his ex-wife was armed, actually. He had taught Rosie to shoot, but knew she was likely to panic. Sven had called the cell phone from the neighbors’ house. Then, well they both knew the rest. Except for the cougar, which was a bit of Disney thrown in by heavy-handed symbolist Nature, the rest was sort of pathetically typical. Husband leaves wife for newer model; newer model realizes husband is old guy after all; leaves husband. Husband has now lost everything—wife, house, respect for self. Starts up old bad habits again, but can’t quit the one that has become like inhale to exhale—the need to protect.

“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately,” said old Hank Thoreau. Rosie guessed she had too, but whereas Thoreau, like Sven, who went into the emotional wilderness somewhat outgunned, returned after proving himself for little more than a year, she surprised herself. Rosie had discovered that life could indeed be mean, but once you have boarded that train of doing without, it is hard to jump off. It seems that a woman, too, is made wealthy by what she can afford to do without.

__________

Norma Gay Prewett taught English for 34 years and recently became RETINO (retired in name only) from the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater. She is now free to do any dang thing she wants anytime she wants, but will probably continue to write, bike, quilt, keep her coop, and meditate at her retreat, Piney Wood Mews. She also co-produces Mindseye Radio, which airs first Fridays at 11 PM on WORT-FM or radio4all.net.

The Silent Witness

Steven Salmon

An excerpt from the novel, The Silent Witness

__________

Stan hid inside the apartment for a couple of days. He began to miss being outdoors in the beautiful countryside surrounding Poynette. Stan reflected back to his adolescent years growing up. The Everest & Jennings new electric wheelchair crept along the gravel road on a cool summer’s day with no clouds in the sky. A farmer cut hay in a field while another farmer raked hay. Alfalfa fields and contoured strips of corn wove through the hilly terrain. Pastures nestled in valleys or alongside steep hills. New ranch-type houses had been built along the road and near the woods giving residents a secluded area to enjoy their privacy.

Stan hid inside the apartment for a couple of days. He began to miss being outdoors in the beautiful countryside surrounding Poynette. Stan reflected back to his adolescent years growing up. The Everest & Jennings new electric wheelchair crept along the gravel road on a cool summer’s day with no clouds in the sky. A farmer cut hay in a field while another farmer raked hay. Alfalfa fields and contoured strips of corn wove through the hilly terrain. Pastures nestled in valleys or alongside steep hills. New ranch-type houses had been built along the road and near the woods giving residents a secluded area to enjoy their privacy.

Stan sat in silence listening to the wind blow, sending strands of drool airborne. He loved to watch farmers bale hay, cultivate crops, harvest and plow. Neighbors honked their horns at Stan. What Stan loved the most was watching a bee land on a sprig of wild parsley or seeing a chipmunk dart across the road. Off in the distance loomed the Poynette water tower.

The wheelchair had a hitch on the back. Stan pulled a wooden drag fashioned out of two-by-fours. Nathan welded a hitch to the wheelchair’s rear end. The drag trailed behind the power chair smoothing out pockets of pebbles. If Stan saw a pile of hay on the road he pushed the broken bale into the ditch.

A farmer installed an entrance to a field to have easier access for his equipment. A load of gravel had been roughly spread over the drainage pipe. Stan spent the whole afternoon grading the entrance by slowly inching his way across the drive.

Stan drove past an olive ranch house. The wheelchair hummed past an ancient barbed wire fence. The fence posts leaned forward and rusty strands of barbed wire clung to the decaying posts.

Beyond the fence lay a narrow strip of tall prairie grass before it turned into woods. Stan saw the orange Poynette newspaper box ahead of him and gradually the driveway became visible. The wheelchair turned into the drive leading straight down into the woods. He paused for a minute before barreling down the hill. Stan saw Nathan on the tower adjusting his ham radio antenna. Nathan erected the tower on a hill overlooking a cow pasture. Stan put a firm grasp on the joystick before going down the hill. He had the biggest grin on his face rocketing down the hill. At the bottom of the hill lay a creek bed, and then the wheelchair climbed a smaller hill opening onto a meadow. Stan passed a brown sheet-metal shed where Nathan stored a John Deere tractor, a plow for plowing snow, a three bottom plow, a disk, a garden tractor, a red Chevy pickup truck and the tan van with the wheelchair lift.

* * *

One day after a thunderstorm Stan drove his electric wheelchair outside of the house. Amber warned him not to enter the newly seeded muddy yard. But he became bored going back and forth in front of the garage. Stan decided to run down the front yard hill for the fun of it. He became stuck at the bottom of the hill and spun his wheels digging the wheelchair deeper in a hole. He heard the front door open and then Stan braced himself.

“Goddammit, Stan, I told you not to go down the hill! You don’t listen! You’re so stubborn! You’re grounded!”

Amber struggled to push and pull the wheelchair up the hill to the porch. She transferred Stan from his power chair to his manual wheelchair taking him inside the house. She took him to his bedroom and left Stan in his room without supper. Amber made him stay in the bedroom until Nathan put Stan to bed.

She spent the rest of the afternoon and evening scraping off mud caked on the wheels, motors, belts and the brakes with a dull butter knife. She dug dried mud from a couple thousand notches on both of the rear wheels. Amber washed the entire wheelchair with a damp warm washrag. She dipped the rag in a plastic ice-cream pail with warm water and soap. Amber stared at the pair of zigzag wheelchair tracks tearing up the front yard, but she reminded herself that her son was like any other teenage boy getting into trouble. The electric wheelchair was clean for school the next day.

* * *

Stan stopped near a metal ramp leading up to the front door when he saw his father climbing down from the tower. Stan’s eyes looked at the newly seeded yard and the oak-stained house situated on a hill.

Nathan and Amber’s vegetable garden lay between the house and the back yard. A pile of scrap lumber was underneath the tower. Guy wires were anchored at different angles throughout the back yard to secure the tower. Sprigs of tender grass sprouted up through the sloping lawn. Woods surrounded the meadow on three sides creating a secluded place. Deer grazed during sunset in the prairie behind the house. A trout stream led farther back into the woods.

Stan heard the jingle of Nathan’s security belt. He turned his head to see Nathan approaching the porch.

Nathan grinned at Stan. “How was your ride?”

Stan blinked his eyes twice and laughed.

“That’s good. Ready to go in?”

Stan blinked yes again.

Nathan smiled. “Fine and dandy. Let me unhook you and we’ll go in.”

Stan nodded.

Nathan detached the pin from the drag and the wheelchair’s hitch. He stored the wooden implement in the garage. When Nathan came back, they disappeared inside the house.

Stan drove inside the barrier-free house. He headed down an entryway that opened onto a spacious living room and a kitchen. Stan raced his chair around a butcher block island in the middle of the kitchen.

Amber yelled, “Stop racing in the kitchen! And don’t go in the hallway if your wheels are muddy!”

Stan drove on the subflooring in the living room.

Nathan helped Amber prepare supper. “At least the bedrooms and hallway are carpeted,” he said.

“And don’t forget the roll-in shower to bathe Stan,” said Amber. “And the sink without a vanity to wash Stan’s hair.”

“Having all thirty-six-inch-wide doors allows Stan to go anywhere that he wants. Wait until I finish the elevator. Then he can roam the entire house!”

Stan smiled looking at the sliding doors in the corridor.

“When I get the basement walls sheetrocked and the rest of the area cleaned up, then I’ll turn my attention to the elevator. But I’ve to get the rocket business going first.”

Nathan had worked as an engineer for General Motors for twenty-one years. But he wanted to try something new.

Stan and Nathan liked shooting miniature rocketships at a beach or a wide open area. He watched Nathan launch rockets in the sky. The puffy white streaks against the blue skies fascinated Stan. Nathan decided to go into business marketing and selling rockets to hobby stores around the country.

Amber and Nathan Richards grew up in Poynette, Wisconsin as children. After they married and discovered they couldn’t conceive, the Richards adopted a baby boy. Slowly Stan’s mother noticed their son had difficulty holding up his head. Doctors diagnosed Stan with cerebral palsy. Some doctors advised the Richards that Stan should be put in an institution.

Amber refused to believe Stan was mentally retarded since his eyes lit up every time she spoke to him.

He always wanted to know why a particular instrument performed a specific function.

Amber bought oatmeal and flour at a mill near their house. The mill sat on the Wisconsin River in a quaint village called Portage. Maples and oaks surrounded the red three-storied building. Posts linked together with rope outlined the manicured lawn and the circular cinder drive.

One day Stan sat in the tan Econoline van waiting for Amber to come out of the mill. He had an intense expression in his eyes watching the buckets gathering water up and going down before pouring the water out.

When Amber saw Stan’s curious eyes pointing to the millrace, she said, “Let me guess. You want to know how the wheel goes around?”

Stan nodded. He didn’t understand how the mill generated power. It wasn’t visible to him.

“The wheel generates power to grind the grain into flour.”

Stan grinned and let out a moan sounding like oh.

The millrace reminded Stan of the white brick farmhouse where he grew up. The millrace and the farmhouse resembled parts of the past that somehow continued to withstand the ever-changing environment. The house sat on a grassy knoll surrounded by farm fields. Stan sat in his manual wheelchair watching farmers toil in the fields until dusk.

* * *

Stan loved to watch Nathan tap Morse code in his office into one of his ham radios communicating to hams across the world. It fascinated Stan; his father communicated with people by tapping on a key.

Stan sat in the mall at a table that displayed the ham club’s equipment.

People watched the hams demonstrate Morse code and how to operate the ham radios.

He was sitting next to Nathan when a stout muscular blond man with red trunks and high-heeled black boots strode up to the table.

The man shook Nathan’s hand.

“Hi, I’m Marko the Magnificent! Is this your son?”

“Yes, he is.”

“Well, I’m the wrestler for the Danco wrestling bear. Would your boy like to pet my bear?”

Stan looked frightened.

“Danco doesn’t hurt people like you; only men who are stupid enough to step into the ring to fight him. Would you like to meet Danco?”

Stan groaned and smiled.

“I’ll be right back.”

Marko disappeared. Several minutes later, he reappeared with the grizzly bear on a leash. A crowd gathered around Danco.

Nathan pushed Stan into the human circle.

Marko took Stan’s right balled fist to pet the bear between the ears. Marko asked, “Can he give Danco a Pepsi and an ice-cream cone?”

“I would have to help him hold it, but it’s doable.”

Someone fetched a Pepsi and a chocolate ice-cream cone from Baskin & Robbins.

Nathan pried open Stan’s right balled fist to place the cone in his hand.

Danco’s tongue licked the triple decker and then sucked the ice-cream cone out of Stan’s hand before it crumbled in his fist.

Nathan then lifted the bottle of Pepsi to Danco’s mouth with Stan’s fist on the bottom of the bottle.

The grizzly bear grabbed the soda pop from Nathan’s hand. Danco stood up on his hind legs guzzling down the ice-cold Pepsi.

Cameras flashed. The next day’s newspaper had a photograph of Stan smiling beside Danco drinking the Pepsi. The caption on the front page read, “A Special Boy Tames Bear.” The article recorded just another of Stan and Nathan’s adventures.

* * *

The members of Nathan’s ham radio club “adopted” Stan. In the summer the hams gathered to communicate in the jargon only they understood: “Oscar,” “Alpha,” “Delta,” “Tango,” “Papa,” “Zulu,” and the rest of the Roman alphabet could be heard echoing under the large tent as the sun glared. All day he and the club members sat under the tent until late evening. Nathan and Stan arrived early the next day to play with the radios.

The Richards helped strike and set up tents since Nathan had a pickup truck to haul the club’s gear. Nathan met the club members at a warehouse to pick up tents and gear for the ham’s showcase, but the building was locked. The men huddled together bewildered searching for an answer.

Stan laughed in the truck when the men came over to the passenger’s side of the pickup.

“All right, what’s so funny,” said Nathan.

The men looked in the direction Stan’s eyes pointed. Their hands rested on their chins thinking what Stan saw they didn’t see.

Suddenly one of the men said, “The back door.”

Stan let out a huge scream.

The man walked behind the sheet-metal building, and the door was unlocked. The tents and gear had been stacked inside the door.

The man yelled, “It’s here!” He waved to the other men to come help. The man carried a bundle of wooden stakes to the truck. He stopped at the passenger’s door and smiled at Nathan.

Stan’s laughter had caused him to slip down in his seat, and Nathan gave Stan a boost before he fell underneath the dashboard.

“Stan saved the day for us!”

Nathan beamed. “That’s my boy!”

Stan had another fit of laughter as he watched the men trudge back and forth loading the truck. When the ham radio club’s relay shack needed to be replaced, Nathan volunteered to do the job of hauling sand to build a cinder block building. The aluminum shack sat on a hill next to a two-hundred-foot steel tower out in the country.

Stan enjoyed the sand hauling; just being around his father was deeply satisfying and, of course, he liked watching the construction equipment.

Nathan took Stan in the pickup early one Saturday morning to meet Jerry to get a dump truck. Jerry, a ham from the club, was building cabins for the Boy Scouts. He planned to borrow a truck to haul sand.

Jerry had dug out a foundation for a scout cabin with a bulldozer when Nathan arrived. One of Jerry’s three dump trucks had broken down. He needed the other two trucks to keep moving earth and finish digging the foundation. Nathan knew Stan had looked forward to riding in a dump truck all week. Stan had ridden in tractors, combines and bulldozers but never rode in a dump truck before. Nathan radioed another ham named William and they met at a roadside café to locate some sand.

William worked as a contractor and knew a job site that had sand. He promised Nathan to have a loader load the sand in the pickup truck. When the men arrived at the development, Nathan and William had to shovel the sand by hand. Stan sat in the truck for two hours disappointed about not having a payloader to load the truck.

Nathan hopped into the cab exhausted, and said, “Sometimes things don’t work out the way you planned.”

Stan nodded. He started to understand what Nathan meant. People like doctors, wheelchair vendors and physical therapists always promised him a new electric wheelchair in two months, but it always took a year to receive a new chair.

Nathan started shoveling out the sand into a pile next to a cement mixer and bags of mortar. No one came to help Nathan.

“And sometimes people never see a person’s hard work. And sometimes you have to grin and bear it!”

At the time Stan wondered what Nathan meant. He worked harder and longer than anyone else to achieve his dreams. People kept putting obstacles in his path. People always said to Stan that he deserved the best, but when he needed a new power chair endless rules and procedures had to be followed. He was just another number to Medicare and Medicaid.

It confused Stan when he had to wait a year to receive a new electric wheelchair or an input, but at the same time people treated him like he was special. To Medicaid and Medicare physically disabled people are just numbers that had to wait their turn to be approved for specialized equipment. But he attended the mall, fairs, circuses and any social outing with his parents. At times a person might come up to Stan giving him money or offering to buy cotton candy or lemonade. He never asked or wanted these gifts that people gave him. It embarrassed and humiliated Stan. He saw himself as a curious normal boy asking questions, not a helpless cute cripple.

Nathan took Stan to ham radio swap meets where he bought or traded radios.

Stan stared at the radio knobs and grunted at Nathan until he explained what a specific knob did. He always wanted to know about everything no matter how small it was. Stan wanted a detailed explanation of what function a knob performed. He didn’t stop his questioning.

* * *

On a cloudy summer’s day Amber let Stan outside in his electric wheelchair to take a ride. She guided him down the steel ramp onto the driveway. Amber stared at the clouds in the sky.

Stan wanted to zoom up the hill when Amber said in a high tone of voice, “Now don’t make me come and have to find you like that time you were driving on Bora Road and a thunderstorm popped up. It was lightning all around us! There’s a thirty-percent chance of rain this afternoon. So you keep your eyes on the skies and don’t go very far. Hear me!”

Stan groaned.

Amber watched the Weather Channel each morning before Stan got up trying to figure out what to put on him for the day. The Weather Channel stayed on the TV all day. When a tornado watch or warning was issued, Amber rushed about the house getting ready to hide in the basement or a closet until the storm passed. If the temperature was too cold or hot, she didn’t allow Stan outside. If she saw a chance of precipitation in the area, Amber didn’t want to have to chase Stan down in a thunderstorm. She dressed Stan too warmly at times in the winter. She knew that Stan loved the outdoors, but she felt that she needed to protect him from the elements.

He didn’t like his mother’s overprotective attitude, but he understood. Stan knew that Amber’s word was final.

“I mean it!”

Stan nodded at her with drool dribbling down his chin before he turned to head up the hill.

* * *

He hated people that he knew were overprotective of him, like Mrs. King. Stan finished eating lunch in the cafeteria. Mrs. King wiped off his mouth and took off the paper towel protecting his shirt. He headed toward the door that led to the back of the school where the students were before Mrs. King stopped him.

“You can’t go out unless you have your coat and a hat on. You wait here and I’ll go get them.”

On days when Stan ate lunch and Mrs. King wouldn’t let him go outside due to coldness, he decided to visit Gina in the school office and flirt with her.

Stan appeared at the school secretary’s office when Mrs. King and the secretary ate lunch. He loved to sit teasing Gina and spending time with her alone.

But Principal Barlow showed up early one afternoon before the lunch ended. He stared at Stan while talking to Gina in his blue dress pants, white shirt, and pink and grey striped tie. The potbellied bald man with thick black bifocals said, “Stan, you shouldn’t be here! Gina is working. Please leave now! And don’t let me see you in the office at this time again!”

Stan left. He sat close to the music room door listening to the band rehearse on the days that he didn’t go outside. Stan felt alone as drool dripped on his shirt. The music played, but his loneliness increased with every beat eating his heart away.

Stan sighed.

* * *

He had saved his weekly two-dollar allowance for three months to purchase a clock radio for his bedroom.

Nathan took Stan to Roger’s Appliance store in downtown Poynette.

A heavyset middle-aged salesman observed Stan grunting to Nathan trying to decide what radio he wanted. The salesman watched them discuss the pros and cons of each brand.

“A General Electric is a wise choice. It’s durable and reliable.”

Stan smiled and nodded at Nathan, who replied, “That’s what I would have bought.”

Nathan pushed Stan to the sales counter to pay the salesman. The sales manager grinned at Nathan when he handed the radio to him. Nathan retrieved Stan’s wallet from his backpack to pay the salesman. Stan giggled and strands of drool hung from his bottom lip.

The manager wrapped the radio in a bag and handed the money back to Nathan.

“What’s this?”

The salesman grinned and said, “It’s a gift from Roger’s Appliance. I feel sorry for him being a cripple.”

Stan squawked and wildly flung his arms in anger at the manager.

“Calm down, Stan. He just doesn’t understand.” Nathan tossed the cash to the man. The salesman yelled, “I didn’t mean to make the cripple upset.”

Fortunately, Stan didn’t hear the salesman’s last comment.

* * *

Stan didn’t like when people were disrespectful and treated him as a cripple. It reminded him of an incident with his neighbor, Eric, who lived in the olive ranch house. Eric’s dad hunted muskrat, raccoon and deer in the large woodsy section nearby. Eric owned a BB gun. He shot at crows or at the bullseye target set up against a tree in the back yard.

Stan was driving his wheelchair on his way home one afternoon when he passed his neighbor’s house. Eric was shooting baskets in the front yard.

When Stan drove by, Eric stopped to stare at him.

He made monkey faces at Stan and yelled, “You’re a frisking drooling goat that needs to be shot!”

Stan kept on driving home. He heard a door snap open. He heard a click followed by a sharp ping. Both shots ricocheted off of the wheelchair’s hitch near the battery. One pellet flew past Stan’s head nearly missing his eye by inches.

Eric’s mother flew out of the front door after she heard the second shot fired. “Eric, you put that gun down immediately!”

Eric’s father Bill raced out of the house. He looked into Eric’s eyes.

“Do what your mother says now!”

Eric put the gun on the ground.

His mother said, “You get your butt in here right now!” She swatted him on his behind as he entered the house.

Bill ran over to Stan. “Are you okay?”

Stan blinked.

“I apologize and want you to know that will never happen ever again, I promise.” He walked Stan down to his house to explain what happened to Amber and Nathan.

Eric didn’t receive another gun until he learned to respect the privilege of having a gun.

* * *

He virtually had no friends all through school. It frustrated him at times not being able to talk to his peers. In his mind, he believed Gina was his “girlfriend.” In his heart he knew Gina was just a good friend. The word girlfriend sounded better in his head than a friend. His ultimate wish was to have a physical relationship with a woman. Stan dreamed of marrying a beautiful girl like Gina and spending the rest of his life with her. He wanted to have sex with Gina and fantasized various sex scenes in his mind.

Stan had a favorite sexual fantasy of Gina giving him a bath. He lay in the bathtub with Gina kneeling next to the tub and washing his entire body. She washed his hair first. Gina then dampened a washcloth with warm water before lathering the cloth with soap. Stan watched her wash all the parts of his body. She smiled at him as she washed his face. Gina proceeded down his body, lathering his arms, hands, fingers, armpits, neck, back, upper torso, buttocks, legs, feet and toes.

He looked up at her. His eyes directed her attention to his erect member.

She washed his testicles and then put the rag on his penis. Gina ran the washcloth up and down the shaft of his member. Gina deliberately went around and around the tip of his cock with the soapy washcloth. When Gina picked up his member to lather the base of his penis he ejaculated.

“You became too excited.” Gina grinned at him before squeezing the washcloth with warm water in between his legs to wash away the soap and semen.

He liked to sit in front of the girls’ locker room imagining a line of naked girls taking a shower after gym. Stan envisioned himself walking into the showers and watching the young women showering. When he had fantasies about women, Stan had the ability to stand and walk. He never wished that he could stand up. But Stan dreamed about having sex in an upright position as he made love. In this sexual fantasy Stan took off his clothes and went down the row of naked girls sticking his member into each girl. Gina was the last girl standing in line.

* * *

During science class a blonde touched Stan’s arm causing a boy to shout, “First comes love, then comes marriage, and then comes another retard in a baby carriage.” Sometimes a girl made eye contact and smiled at Stan. He flashed his big grin at the girl before he nodded.

One morning before second-hour Stan drove up to Gina’s locker to say hello. Robert pressed his body against Gina’s as they kissed.

Stan grunted.

Gina pulled away from Robert, and said, “Hi, Stan.”

She smiled.

He grinned.

Robert stared at Stan and said, “Go away, retard!” He glared at Stan and pointed to his bulging member. “You and I know what she wants. And that’s meat, pal! I’ve plenty of it and you don’t! So, leave!”

Stan backed his wheelchair away with his head bowed down.

Gina glared at Robert and tapped her right middle finger on Robert’s brawny chest. “Don’t you ever treat Stan that way again or I’ll break up with you. Stan will always be my friend and you better get used to it!”

Robert stood dumbfounded against Gina’s locker watching Gina run to catch Stan to apologize for Robert’s behavior.

She hugged Stan. Gina walked Stan to English class and talked about the English quiz they had next hour.

Stan instantly forgot Robert’s stupid comment.

* * *

Robert and some of his friends smoked pot under the gym bleachers the day before Christmas vacation.

Stan drove around the indoor track when he saw Robert. Stan said “Hi” to Robert.

The boys blew smoke at Stan and called him names. But Principal Barlow refused to take any action against the boys out of fear that they might hurt Stan.

After Christmas, Stan took Robert aside to express his feelings.

Robert patiently watched Stan’s right index finger spell out words on his communication board and forming a sentence. Robert read the words out loud: “If / you / ever / do / that / again / to / me / I / will / tell / Gina.”

Robert looked at Stan and said, “You go right ahead. Do whatever you want! I don’t care what you do! You moron!”

* * *

Stan lay in bed thinking about Gina. He woke up early Saturday mornings to have Nathan take off his pajamas.

His father had earlier discussed the birds and the bees with Stan, allowing him to explore the sexual pleasure of manhood. He covered Stan up before closing his bedroom door. In a couple of minutes Stan kicked off the covers. He stared down at his penis watching it become aroused. He imagined Gina lying naked beside him. Stan pictured her round firm breasts and taut nipples brushing against his skinny chest. He envisioned her smooth pale stomach and the hairy black triangle in-between her legs. Before Stan knew it he felt a tingle at the tip of his penis. Stan watched semen burst out of his member as he imagined he was having intercourse with Gina. It was these fantasies as well as Stan’s first wet dream giving him a physical connection to Gina that he would always remember.

In Stan’s sexual fantasies, he pretended to be Prince Charming who swept girls off their feet. Stan was surrounded with girls dressed in skimpy outfits at his beck and call. He wanted a physical relationship with a girl, but he knew deep down inside what he thought to be a horrible reality: no girl would ever kiss him or press her breasts against his drenched shirt.

Stan dreamt about taking Gina out on a date. He saw himself being with Gina at the movies and putting his arm around her shoulders.

She gave Stan a peck on the cheek causing Stan to laugh and disrupting the entire theater.

In the dream, people stared at the beautiful girl holding hands with the “cripple.”

* * *

Stan raced his electric wheelchair in mud or snow just like boys riding their bicycles. He wanted new records of Michael Jackson, Boy George, and The Talking Heads to play loud in the privacy of his bedroom with his parents threatening to turn the volume down. He dreamt about having friends to “hang out” with like his peers did on the weekend. Stan wanted to date. In his future, Stan pictured himself attending college, having a job and getting married just like anyone else.

Stan knew how society viewed the physically disabled; they were “special.” He cringed when he heard the word “special.” He always had to laugh when he was called “special.” If he could have talked, Stan would have said, “Go fuck off!”

No one believed he attended school except for his teachers, classmates, Principal Barlow and his aide, Mrs. King. He developed a hard exterior shell. Some people believed that Stan was delicate and innocent, but they hadn’t experienced the endless name-calling he endured each day at school. Stan had to build a wall to protect himself or the constant attacks would have eaten him alive.

* * *

The VFW gave a Christmas party for the disabled children in the community.

Stan’s bus driver, Sue Pleasant, organized the party in early December. Sue had a big heart for the children who rode her bus. She sang songs, made homemade apple butter and cookies for the children on Halloween. Her idea of Christmas was to get the children and their families together for a turkey dinner. Santa Claus came bringing presents. Pictures were taken with Santa.

He was tired of being “special.” Earlier that day a boy at school had called Stan a retard bastard.

People’s noble deeds embarrassed Stan like when Santa Claus gave him a stack of candy canes at the VFW Christmas party.

He saw the Easter Bunny hopping down Main Street. Stan looked the other way to avoid being hugged by the Easter Bunny.

When the Poynette high school eagle mascot embraced Stan after Robert threw a last-second touchdown pass to beat Point, he feared that Gina saw the Eagle hugging him.

But she didn’t see the embarrassing moment. Gina ran over to Stan to get him to join in the celebration taking place at midfield.

At times he didn’t mind clowns coming up to give him candy. One of the few perks of having cerebral palsy was going to places with Nathan and receiving candy from people. Stan rode in the pickup when Nathan cashed a check at the bank. He grinned from ear to ear at the bank teller. The teller put a Dum Dum sucker in the envelope of the deposit. Before Nathan drove away he took off the wrapper from the sucker and popped the Dum Dum into Stan’s giant mouth. Stan laughed.

When Nathan pulled ahead he said, “You’re way too old to be getting a sucker, you know. You’re thirteen years old for heaven’s sake.”

Stan bowed his head feeling ashamed, but he enjoyed sucking on the cherry Dum Dum. Stan imagined the sucker to be a woman’s nipple.

Stan liked going into the Ace Hardware store on Main Street since Harold Swanson gave away free beef jerky sticks to children who came into the store.

Gina helped Harold on Saturday mornings ring-up customer’s purchases while Harold restocked the selves. It gave Gina a way to earn extra spending money to buy the Chic jeans she always wore and to afford pizza at Happy Joe’s.

Before Gina started working on Saturdays, he sat in the truck when Nathan walked inside to buy what he needed.

Stan liked to watch the traffic pass by on Main Street as he sucked on his Dum Dum. He waited for Nathan to return.

Stan entered the store howling.

Harold dropped a bundle of copper fittings on the floor.

Gina knew immediately who it was without seeing Stan. “Stan is here. I’d know that howl anywhere.”

Stan yelped and laughed.

She came over to hug Stan.

“You always scare me half to death when you howl like that,” Harold said.

Nathan replied, “I’m sorry about that, Harold, but when he sees Gina he goes crazy.”

Harold laughed.

Gina said, “Are you ready for the history test on the Industrial Revolution on Monday?”

Stan blinked.

“I haven’t studied for it yet. Mrs. Andrews is the most boring person I know! I hate her pop quizzes. I wish that I had your photographic memory, Stan. You’ll ace the quiz.”

Stan giggled.

“Be right back, Stan. I’ve got to ring-up a customer.” She walked behind the cash register to ring-up a customer’s purchase before she returned to Stan. Gina watched Stan point to letters on his communication board spelling out words to her. Sometimes she laughed or screamed, “That’s not true!” She stopped talking to Stan when a patron had to be waited on.

Sometimes Gina didn’t always have time to speak to Stan.

He worried Gina didn’t want to be friends anymore. Stan moped the rest of the day wondering if he had done something wrong.

The next day Gina talked to Stan like nothing had happened. Their friendship reminded Stan of a giant rabbit’s foot he kept dear to his heart.

__________

Steven Salmon has severe cerebral palsy. He uses a voice recognition computer since he is unable to use his hands. Steven uses Morse code and a word prediction software program called CoWriter. He writes every day (a process he has shared on YouTube). Steven has published three books, Buddy Why, The Unusual Writer, and Cat’s Tail. He has a Bachelor of Science in English from the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point. He also has an associate degree from Madison College where he freelances as a writing assistant. His mission in life is to educate people that the severe physically disabled are and can be valuable contributing members of society if given a chance to succeed. Currently, he is writing his sixth book. He loves basketball and the Green Bay Packers. Steven lives in Madison, Wisconsin.

The Tiger’s Wedding

James Dante

An excerpt from the novel, The Tiger’s Wedding (Martin Sisters Publishing 2013)

[All of the travel literature described Korea as the “Land of the Morning Calm.” So naturally when Jake St. Gregory, a thirty-year-old accountant from Burbank, California, accepts a teaching position in Seoul, he expects a serene escape. Instead, he finds himself in a chaotic relationship, hospitalized, scrambling for money, and then jailed. His pending deportation should come as a relief. But Jake can’t bear the thought of losing Jae-Min, the woman who is the one source of true happiness in his life. Jae-Min, the wife of an abusive husband, has her own turmoil to resolve. Torn between the old Korea and the emerging one, between kimchi and McDonald’s fries, she symbolizes that country’s lost generation. In this tale, set during a pivotal time, their mutual search for happiness draws them together. Ultimately, it might be a fracturing nation that keeps them apart.]

__________

Jae-Min never thought of herself as mysterious or complex, so, naturally, she enjoyed my treating her as such. Photographs and objects around Sun-Hee’s home prompted my curiosity, a few times leading to answers too candid for my comfort.

Sun-Hee’s spare bedroom, before converting it into a mini-classroom, had the effect of a time capsule. In addition to the keepsakes, she held on to the small black-and-white TV once the sibling magnet of their childhood home. As a teenager Jae-Min spent much of her life in front of that old Samsung. With it, the broader world pierced her countrified existence. Jae-Min watched the reports on the assignation of President Park and the pro-democracy movement in the city of Gwangju, close to her own town.

Even more captivating, ABBA was conquering the international music world. The American armed forces channel often televised the band’s concerts. Jae-Min never missed a broadcast. She showed me her vinyl copy of Dancing Queen, which she had as a girl played and replayed until scratches overtook the music. Sadly, she must have realized that the four Swedes would probably never visit Chollanam-do, the southwestern region of Korea known mostly for its melons.

Jae-Min’s maternal instincts were encouraged early on. Every morning she awoke at five with her mother and elder sister. Before school they made certain that a whole day’s worth of rice had been cooked, that enough barley tea was brewing, and that each of the younger heads got scrubbed and checked for lice. By five a.m. her father would be starting the early church service. Although the ministry had insulated them from the worst sort of poverty, they never prospered much above their neighbors.

She flattered her father with talk of joining the ministry, though her parents doubted the rural community would easily accept a woman of the cloth. Jae-Min set out to direct the congregation toward heaven, not with thundering oratory but with music. Three times a week, she played piano and sang before the small but intense group. She saved up her money and purchased a cheap violin, and before long her nimble fingers found the right harmonies.

During her last year of high school, the church hierarchy relocated Reverend Oh and family to one of Seoul’s poorer areas. His mission was to capture as many of the Pope’s wayward sheep as possible. Jae-Min soon realized she lacked the zeal to follow her father’s calling so closely. Her love of music, however, continued to grow. Right after high school, with the help of a scholarship, she began her music studies at a small Christian university.

By the time Jae-Min finished her studies, Sun-Hee had become old enough to take over Jae-Min’s chores. By then, in the eyes of Jae-Min’s parents, every single male at church became a potential catch.

A relatively young man named Mr. Kim joined Reverend Oh’s church. He was the mechanic who kept their truck humming along. Jae-Min and the man had met at church but never really talked until one winter night when he came to the house with his jumper cables. Of course, her father would’ve preferred his daughter meeting a university graduate, but she was after all twenty-four, and the man did earn a decent living with Hyundai Motors.

At her mother’s insistence, Jae-Min agreed to host a dinner for the two families. Mr. Kim didn’t exactly, as they say, sweep Jae-Min off of her feet. He did, however, appeal to her with his strong looks and rugged manner. A woman is almost certainly flattered and amused when this type of man plays the part of the perfect gentleman. When they started dating, Mr. Kim began attending church regularly, a bargain price for securing a virgin.

A combination of his pressuring and her curiosity led her to a downtown hotel where he awaited. Her life soon changed in ways unexpected. With each encounter, the place between innocence and marriage grew more distressing for her. Then one day the affair became the favorite topic of church chatter, causing the parish males to begin looking upon her with that peculiar combination of contempt and interest.

Although the thought holds great appeal, there was no point in my believing she never loved him. Of course she loved him. What livable choice did she have?

The nation changed during the course of their marriage. Martial law ended. Despite the deep boot prints, democracy sprouted from the Korean soil. They built structures that seemed to reach for the heaven they lacked on earth. University women began seeking careers as well as men with good earnings potential. Jae-Min sensed her own life contrasting with all of this. For this reason she embraced the opportunity to teach at Ripe Apple Language Institute. Her husband allowed her to work, providing she kept up on her domestic duties. She thought the extra money would pave over the potholes in their marriage. Instead, expectations from both of them grew. At some point she must’ve realized that she was trying to pave over a canyon.

Now she talked of divorce.

__________

James Dante is originally from Western New York, a place where the snow is relentless, the families are close, and The Holy Trinity could refer to Pizza, Wings, and Subs. For most of his life, however, he’s called Northern California his home. An academic late bloomer, he completed his BA from the University of California at Davis at the age of twenty-eight. International relations proved to be a fine field of study for becoming aware of the broader world and for sounding smart at dinner parties but for little else. After escaping a monotonous government job, James caught the teaching bug in South Korea. There he ended up teaching English at three language schools near Seoul during the mid-1990s and found himself intrigued by the culture and the people. This is how the idea for The Tiger’s Wedding came about. James’s fiction has appeared in literary journals such as Rosebud and Toasted Cheese. The Tiger’s Wedding is his first novel. When James isn’t teaching adult education classes or promoting his book, he’s working on the rough draft of his second novel, which will be set in Moscow.

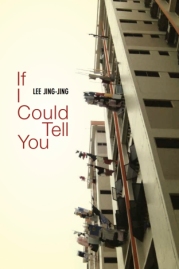

Telling Time

Lee Jing-Jing

An excerpt from the novel, If I Could Tell You (Marshall Cavendish Editions 2013)

[When nothing is really yours, not even the flat you grew up in, just where do you call home? The residents of Block 204 have a few months before their building is torn down, before they are scattered throughout Singapore into smaller, assigned flats. All of them know they will still be struggling to fit their lives into the new flats years later but no one protests. No one talks about it even as they are slowly being pushed out of their homes. Not Cardboard Lady, an eighty-year-old woman who sells scraps for a living. Not young Alex, who is left homeless after a falling out with Cindy. Not Ah Tee, who has worked at the coffee-shop on the ground floor of Block 204 for much of his adult life, and whose reaction to the move affects his neighbours in different ways. For some, the tragedy that occurs during their last days in Block 204 is a reminder of old violence, aged wounds. For others, new opportunities transpire. If I Could Tell You is about silence, the keeping and breaking of it, and what comes after.]

__________